Andrew Mynarski Poster

Introduction

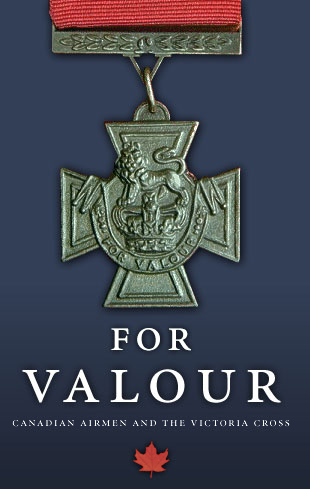

Winnipeg-born Andrew Mynarski was the first member of the Royal Canadian Air Force to receive the Victoria Cross. His act of bravery aboard Lancaster bomber KB726 in World War II earned him a posthumous Victoria Cross.

The Lancaster

The Avro Lancaster was a British heavy bomber first built during WWII. It took a crew of seven (including two gunners, a pilot, navigator, bomb aimer, radio operator and engineer) to operate the bomber, which was primarily used in night missions. Thousands of Lancasters were built during the war, over 400 of them in Malton, Ontario.

Bailing

If the pilot decided the plane couldn’t land safely, he would order the crew to parachute to the ground. The pilot would try to keep the plane level long enough to give the crew time to jump, and would normally be the last to jump.

Most of the crew would escape through a front escape hatch, while only the gunners would escape from the rear. The rear gunner had a small opening in his turret through which he could get in and out.

Rear Gunner

The rear gunner sat in a tiny cramped turret. He was shielded from the outside by thin plastic (called Perspex); many gunners would remove it for the sake of better visibility. Exposed at high elevations, the turret could get very cold.

Tall men did not become gunners. It was also so crowded in the turret that even an average-size soldier couldn’t keep their parachute inside with them.

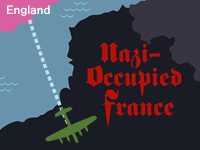

D-Day

On 06 June 1944, exactly one week before Mynarski and A for Able’s mission, the Normandy invasion (better known as D-Day) took place; over 130,000 Allied troops stormed the French shoreline. The goal of the A for Able’s mission on 13 June was to bomb a rail marshalling yard near Cambrai, France. This would help the Allied forces by disrupting the movement of German troops and supplies.

Radar

Some fighters were equipped as night fighters, which meant they had radar to help locate planes in the dark. On the Junkers 88 night fighter, the forward-firing guns were removed to make room for the radar. They used guns that were angled upwards, called Schräge Musik.

A searchlight could be paired with ground-based radar to target planes. If it found a plane, other searchlights without radar would target the same plane (“coning” the plane) to free the radar-targeted light to find other bombers.

Superstitions

A lot of bombing crews were superstitious. Many would have good luck charms to bring along on operations. Urinating on the Lancaster’s rear tire before taking off was also considered good luck.

Night Operations

During a night operation, the greatest defense was staying hidden. Different planes on the same operation would be sent by different routes using different turning points. Communication was kept to a minimum, because the enemy forces might detect the radio signals. Gunners were ordered to not fire upon enemy fighters until fired upon, because the muzzle flare could give away their position.

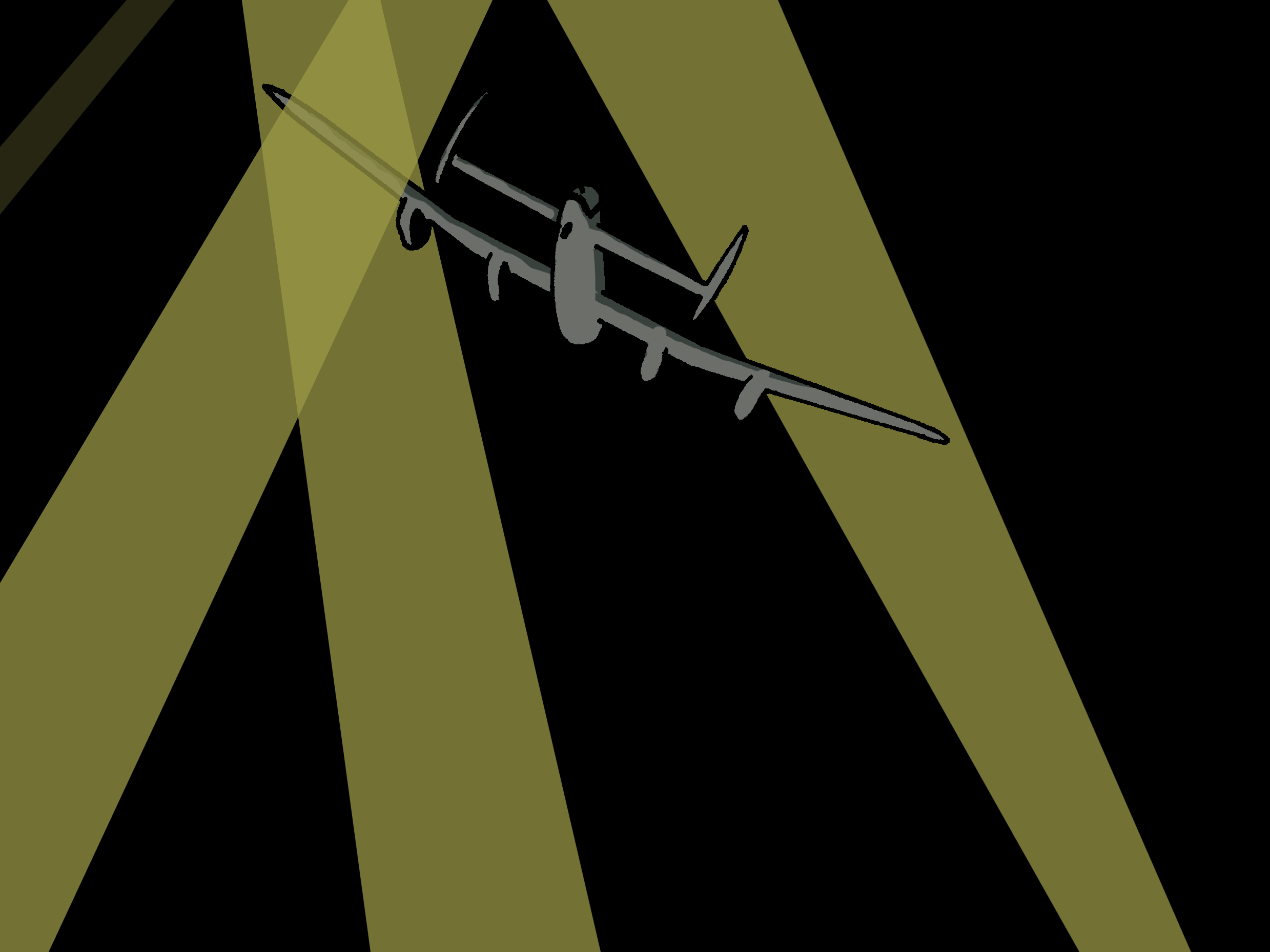

If a bomber was coned by searchlights, the gunners were trained to close one eye to keep their night vision. If the pilot successfully escaped the searchlights, they needed to be ready to spot night fighters.

French Resistance

During World War II, many French citizens cooperated with the Allies. Of the Mynarski crew that bailed, two were found by German soldiers and put in prisoner-of-war (POW) camps. The other four (including tail gunner Pat Brophy) were found by the French resistance. Brophy was provided with a place to hide out and given forged French citizenship papers. It took almost four months to arrange for his passage back to England without alerting the German authorities.

Commemoration

After hearing Pat Brophy’s account of Mynarshi’s actions, Pilot Art De Breyne put in a request for Andrew Mynarski to be awarded for his actions. Mynarski was awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously, and the medal was presented to his mother.

In his native Winnipeg, Andrew Mynarski VC Junior High School is named in his honour. A statue of Mynarski was erected in Middleton St. George, England, where the Moose Squadron was stationed. In Hamilton, Ontario, a reconstructed Lancaster has been dubbed “Mynarski’s Lanc.”

Spotlights

To spot bombers on night operations, the Germans used several searchlights to “cone” a plane – create a cone of searchlights directed on an aircraft. If a plane was spotted, then German fighters and anti-aircraft guns could target it.

Elevation

The Lancaster could reach a height of over 8000 metres (26,000 feet). The plane wasn’t pressurized, so the crew needed to breathe from air masks at elevations over 2500 metres. At low elevations, bombing operations were more dangerous but more accurate, while higher elevations were safer but bombings were less accurate. Choosing the height of a bombing operation always involved that trade-off.

The crew of the A for Able was on an operation that called for a 1500 metre bombing run, and was at 2000 metres when they were shot.

Moose Squadron

The 419 bomber squadron was named after Wing Commander John “Moose” Fulton, the first commanding officer of the squadron. He had more than fifty bombing sorties and was shot down flying back from Hamburg, Germany. At the time of Mynarski’s death, the squadron was flying out of Middleton St. George in northern England.