William Bishop Poster

Introduction

William “Billy” Bishop was a highly decorated airman and one of the most legendary flying aces of the First World War. In his blue-nosed Nieuport 17, Bishop was unmatched in his flying and shooting skills, earning 72 victories by the end of the war.

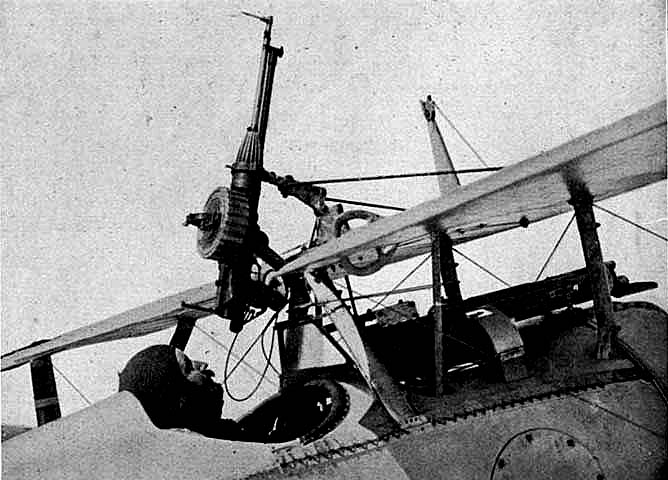

Lewis Gun

The Lewis gun was a machine gun used during the First World War. It was used in the trenches and also mounted on aircraft for combat. The Lewis gun could fire at 500 rounds per minute and was loaded with a drum magazine, which held bullets in a helix (spiral staircase) shape.

Canadian Corporal Joseph Kaeble received the Victoria Cross for driving back 50 German soldiers when most of the soldiers in his Lewis gun section were wounded or dead.

Nieuport

Billy Bishop was flying the Nieuport 17 at the time of his attack on the German aerodrome. This maneuverable biplane came equipped with a 110-horespower rotary engine; the wings and most of the body were made of wood and treated canvas, and were structurally supported by cables. The nose on Bishop’s plane had been painted a distinctive blue.

Rotary Engine

The rotary engine was an engine where the crankshaft stayed still and the cylinder block spun around it. The spinning cylinder block acted as a stabilizer for the plane, like a gyroscope. The rotary engine was common in early planes. It fell out of favour when engine speeds became so fast that the centrifugal forces would have pulled the engine apart.

Cavalry

Before joining the flying corps, Billy Bishop spent some time in the cavalry, because he had experience with horses. For years, cavalry had been a vital component of the army, but in the First World War, use of trenches, artillery and barbed wire made cavalry charges nearly impossible.

Aerodromes

Because the front lines of the war could shift quickly, aerodromes had to be mobile. As a result, hangars were created using large tents so that they could be quickly assembled, taken down and/or relocated.

Bloody April

In April 1917, the Royal Flying Corps lost over 200 aircraft, the worst month for the RFC of the entire war. During this time, a British pilot would be shot down after a total (on average) of 17 hours in the air. The Germans had superior planes at the front lines, a problem the Allied forces did not overcome until later in that year with the production of the Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5 and the Sopwith Camel.

Biplanes

Biplanes had two sets of wings – one above the other, with support bars connecting the two. Because early plane wings were made of wood and canvas, two sets of wings were necessary for structural strength. The Nieuport was a sesquiplane, meaning one of the sets of wings was much smaller than the other. Monoplanes started replacing biplanes as engine speeds increased and more of the planes were made out of metal.

Visibility

Visibility was an important element in air tactics. Sometimes just by approaching a plane from the right direction, a pilot could keep hidden until it was too late. In the design of a plane, the size and position of the wings had to be taken into account. Larger wings made the plane more maneuverable, but also blocked more of the pilot’s field of vision.

Flying Ace

The term “ace” originated during WWI. It first appeared in French newspapers as “l’as” a term used to describe successful athletes. It came to refer to any pilot that downed five or more enemy aircraft.

Albert Ball

Albert Ball was a British flying ace who achieved 44 aerial victories in both Neiuport 17s and Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5s. He was a relatively secluded man, known amongst his comrades for playing the violin and tending a small garden. Ball’s airplane was recognizable thanks to its unique red nose. He was shot down over German territory in an S.E.5, died on 07 May 1917 and was buried by the Germans. At the time of his death, he was the top British flying ace.

Starting the Engine

The engine on early planes needed to be started by a mechanic who would spin the propeller(s). Car engines have an electric motor to “turn over” the engine and make it start, but for early planes, the convenience of a starting motor was not worth the extra weight.